A NEVER-ENDING STORY Stephanie LaCava approaching a Pierre Bonnard painting through the lens of Marguerite Duras

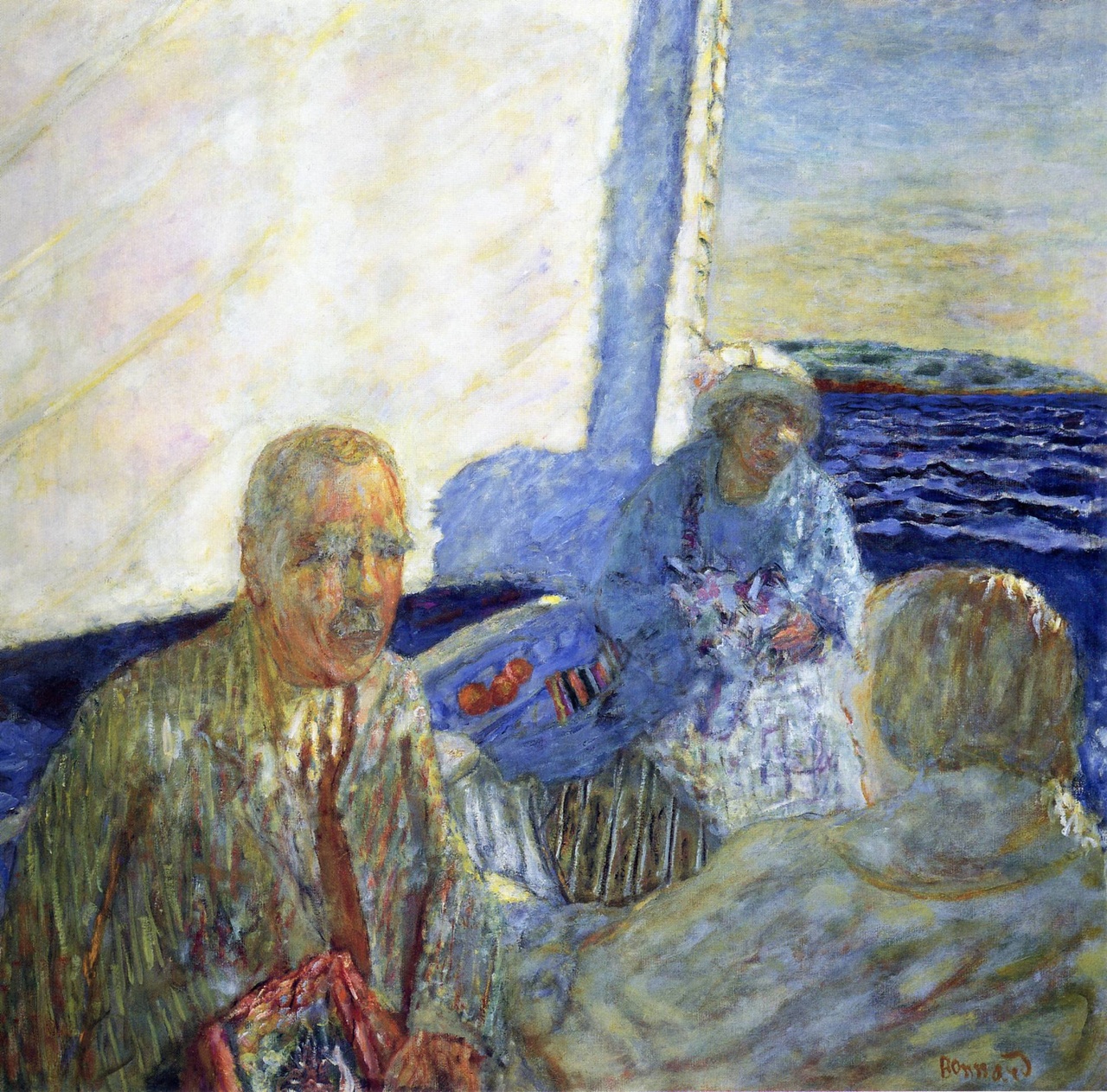

Pierre Bonnard, “Voyage en bateau” (Sailing Excursion), 1924

“No, it wasn’t a Monet or a Manet,” reads the self-reflexive first line of “Bonnard,” the eleventh text in Marguerite Duras’s Practicalities. [1] Duras opens by momentarily questioning her own declarative title. The collection of 48 pieces presents itself in material book-form but is not so much a book. Duras wrote it, but didn’t write it.

First published by Éditions P.O.L. in 1987 with the French title La Vie matérielle, the project began as a series of recorded conversations with French author, screenwriter, and filmmaker Jérôme Beaujour. The recordings were transcribed and reworked as prose, a final edit done by Duras. It is still an exchange, but one with an absent interlocutor. The titles are the only signposts, acting as spectral guides. “I don’t have general views about anything, except social injustice,” Duras says, declaring the impermanence of her words. “I don’t drag the millstone of totalitarian, i.e., inflexible, thought around with me. That’s one plague I’ve managed to avoid.”

Duras is aware of the politics of revision, of looking backward to reconsider. Sometimes this requires the evaluation of one’s contemporaries. Her extensive dialogues and interviews with fellow artists are well-documented in both periodical publications and critical works. She has been in conversation with Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Jacques Lacan, Maurice Blanchot, with the essayist Viviane Forrester, and with the writer and activist (and her ex-husband) Dionys Mascolo. Most often though, Duras has conversed with herself.

In Practicalities, “Bonnard” comes after “The Black Block” and before “The Blue of the Scarf.” In “The Black Block,” Duras says that writing is the opposite of telling stories: “It’s telling a story through its absence.” Hers is a world with a black block at its core.

Post-Bonnard, black turns to blue, a shade only Duras knows. In “The Blue of the Scarf,” Duras explains that the author is the only one who can ever know the exact color of something she’s written about. Then, a Blanchotian turn. Duras acknowledges that Blanchot says she uses intermediary characters – like Jacques Hold in The Ravishing of Lol Stein – to become closer to other characters The ever-present but silent Beaujour is this, too. Nearing the close of “The Blue of the Scarf,” Duras writes, “After the dinner at Lol Stein’s the colors remain the same, the colors of the walls and those in the garden. No one knows yet what is just about to change.” Not even she.

One of Duras’s novels is called Blue Eyes, Black Hair. No one else can tell you what its protagonist looks like; only the author knows. But “Bonnard” is different. There is certain evidence of the unnamed ekphrasis detailed therein.

“The making of pictures and books isn’t something completely conscious,” Duras says in “Bonnard,” “and you can never, never find words for it.” Once again, she uses self-cancelling language, denying writing as she writes. She goes on to outline the painting of a boat with a family inside. She tells us that she’s seen it in Bern, Switzerland, in the house of unnamed collectors, that the couple were in continued dialogue with Pierre Bonnard, who insisted on getting the canvas back in order to change the sail. The collectors eventually gave in. Time passed and when Bonnard returned it, considering it finished, they determined how “the sail had swallowed up everything, dwarfing the sea, the people in the boat and the sky.” Duras offers no more information. No colors.

Bonnard’s late-stage revision is likened by Duras to the future-next sentence in an author’s unwritten book. Once down, it can alter the entire story. She says, “And the next morning you find you’ve sat down to a different book.” She gives us nothing more on the Bonnard. No colors.

It seems that Duras had visited Villa Flora, the storied home of Arthur and Hedy Hahnloser. Arthur, an ophthalmologist and Hedy, herself a painter and self-taught critic, were known for their support of and engagement with living artists. They would take on both public and private roles, sometimes acting as intermediaries between artists and other collectors. In their time, this meant post-Impressionists like Félix Vallotton, Édouard Vuillard, and Bonnard. There are varied accounts of either Vallotton or the sculptor Alberto Giacometti’s father, the Swiss painter Giovanni Giacometti, as having first introduced the Hahnlosers into the scene. The couple became known for hosting “revolution coffee,” a series of talks at Villa Flora sustained by endless cups of black coffee.

Through their engagements with leaders of the Nabi and Fauve movements, the Hahnlosers encountered many works in those styles. Duras’s “Bonnard” describes only one, without mentioning a single color. Indeed, in that painting, the entire upper right quadrant is filled with the white shades of a sail.

There is no sign of pentimenti. No evidence of the reconsidered painting. No faint lines to tell its story, only a sliver left of the sky and sea. There are three people and a dog on the boat. To the left is a man with thick eyebrows and moustache, his head set against the sail. In the crease of his neck is strontium yellow that cedes to neutral skin and blue-gray facial hair. He is wearing a jacket that shows almost iridescent. There appears to be a book in his hand, words, which no one will ever see. The page as everlasting intermediary.

This man is facing a woman who turns her back on the viewer. Her whole appearance is ghostly, pale pearl-like, nearly the same color as the enlarged sail. Across from her, in the background, sits another woman holding a lavender dog. She is wearing a white hat and her dress is aquamarine. The water behind her is blue.

Stephanie LaCava is a writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Artforum, The New York Review of Books, Vogue, and Interview. Her debut novel, The Superrationals, was published by Semiotext(e) in 2020; her latest, I Fear My Pain Interests You, by Verso in 2022.

Image credit: Public domain

Note

| [1] | Quotations translated into English by Barbara Bray. |