RUPTURES, REROUTINGS, CONVERSATIONS, AND CLAY Irmeli Kokko on the Value and Volatility of Artist Residencies

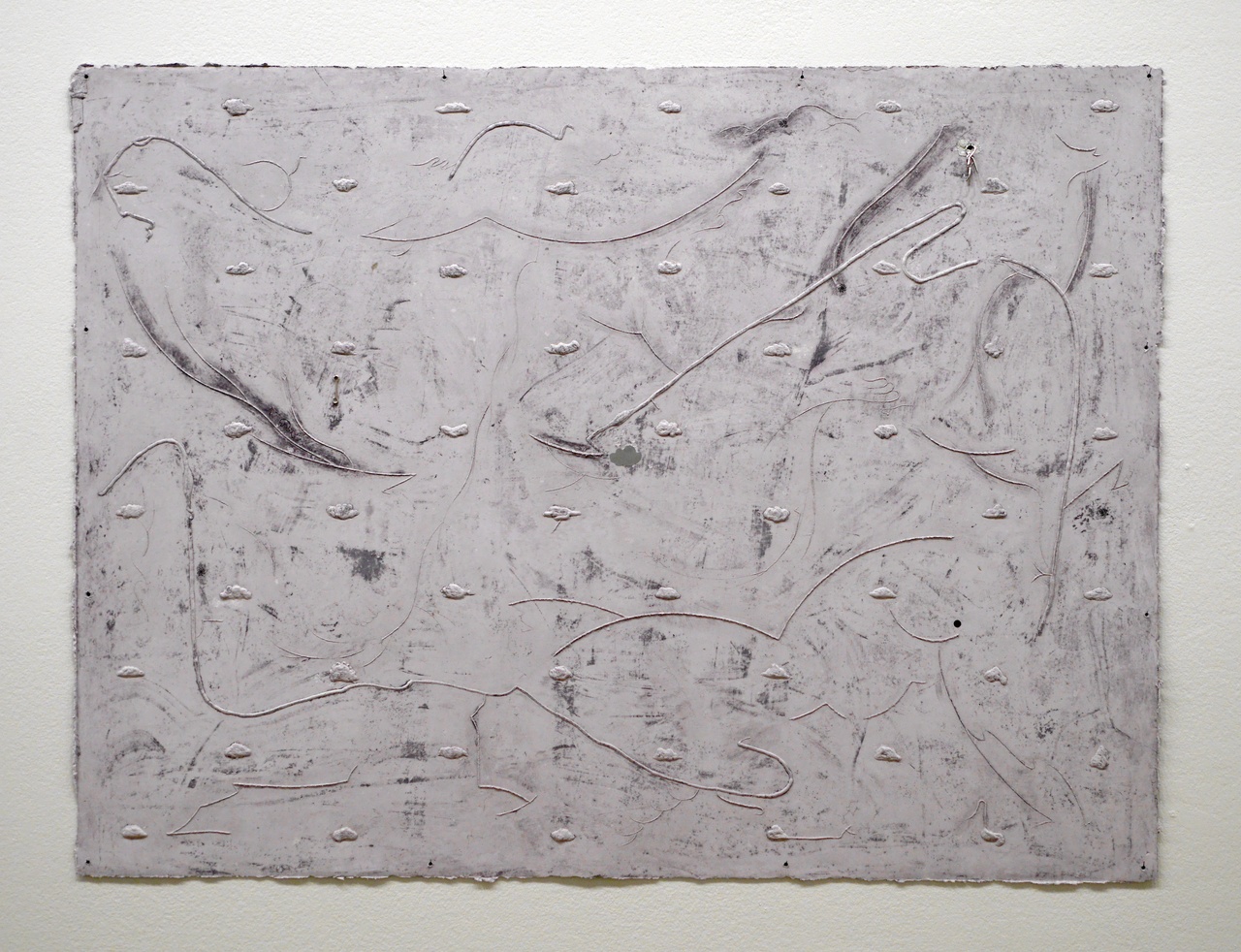

Océane Bruel and Dylan Ray Arnold, “Today was too windy for any thought to stick by, but too calm for a brainstorm,” 2020

In June 2020 an open call invited artists from across the globe to participate in the Trans-Siberian Railway Trip. Organized by the Helsinki International Artist Programme (HIAP), the en route residency was scheduled for the summer of 2021 but had to be postponed by one year due to the pandemic. Starting from Helsinki, participants were to traverse the enormous expanse of Russia, from Moscow to Vladivostok. The curatorial idea was to explore the concept of slow travelling – its possibilities, means, and constraints – as a condition for artistic work. Out of 423 applicants, 15 artists were selected to embark on the journey; among them were Océane Bruel and Dylan Ray Arnold, both based in Finland, where they work as a duo and individually. The two artists’ projects can be described as poetic investigations into the politics of materiality and corporeality, and their process is deliberately open, welcoming uncertainty and elements of the unconscious. Simultaneity and the superposition of different layers of sensations, rhythms, and materials are characteristic of their approach – as is a certain sense of in-betweenness, informed by experiences of transit, of moving from one place to another. The duo’s first collaborative exhibition, “Touristes Tristes,” consisted of a series of sculptural objects and image-based works which the artists described as mixed-media fieldnotes of a hiking trip in the Swiss Alps in 2014. The show was followed by other travel-related exhibition projects, such as “Be Sure to Collect All Your Longings and Let Me Crash on Your Shore” and “The Slow Business of Going.”

Against this backdrop, the Trans-Siberian Railway residency provided a perfect opportunity for Bruel and Arnold to continue their common practice. The two artists were eager to explore the train ride both as an everyday situation and as a sensory experience; they were intrigued by the idea of being in motion, interrupted by occasional stop-overs at unfamiliar places, by the social aspect of travelling, including all the messages, letters, drawings, and postcards that would be composed on the way in order to capture and share the anticipated plethora of passing impressions.

Mustarinda – Preparations and Ideas

Preparations for the trip began in March, four months prior to the scheduled departure date, at the Mustarinda Association, an interdisciplinary residency center in the rural northeast of Finland. On-site and remote meetings were organized for the 15 participating artists to collectively develop ideas on how everyday life and art-making would be possible on the train. Bruel and Arnold were particularly interested in how they could expand the project beyond their own, personal experience. They researched the rich history of travelling artists, as well as the ways in which remote landscapes and life were rendered in drawings, books, and photography. The two artists also invited friends and relatives to, in a way, participate in these travels by asking them which places, shops, cafes, artworks, or museums they would recommend along the journey route.

Mustarinda is a special place. Extra effort is needed to get there. The house, a former school building, is located on a hill at the edge of the Paljakka Nature Reserve, which is one of the few untouched fir forests in Northern Europe. A shared kitchen provides a platform for food-making and casual conversations with participants from other residency programs hosted by the association, with artists, researchers, and scientists from various fields. Working rooms are spacious. The program’s self-proclaimed mission is “to promote the ecological rebuilding of society, the diversity of culture and nature, and the connection between art and science.” At a remove from the rush of the digital world and surrounded by a wealth of wildlife, including rare species which today find their retreat only in very old woodlands, the place resembles a sanatorium, a protected space where the world can still feel in pretty fine order.

After a productive two weeks of preparations, the peaceful life in Mustarinda was disrupted by bad news: as a result of Putin’s attack on Ukraine, the Trans-Siberian Railway Trip residency project had to be cancelled. For the first time since 1939, when Russia attacked Finland and the Winter War broke out, the 150-year old train traffic route between Finland and Russia was shut completely.

Taattinen – Leisure and Work

The majority of their plans for the coming summer so abruptly thwarted, Bruel and Arnold decided to apply for a one-month residency at Taattinen Tila farmhouse, which – in addition to hosting around forty B&B holiday guests – also hosts a few ceramists and artists. The house is located on the west coast of Finland, a region famous for the wild clay in its soils. Artists in residence and vacationers share the farm with ten sheep, a goat, several chickens, and roosters. Bruel and Arnold shared the large pottery studio with two ceramists and divided their time between work and leisure. Long walks by the sea alternated with disciplined work phases, spurred by the zeal of their studio-mates, for whom the month at the Taattinen house meant a rare opportunity to work as ceramists during their summer vacation from teaching. The residency ended with a group exhibition, showcasing the creative output of all participating artists.

The sculptural installation Deeper Sleeper by Bruel and Arnold was exhibited on the floor of the pottery studio; it consisted of various objects made of wild clay, partly manipulated with fingers and different tools, and included cups, patterned flat tile squares resembling archaeological letters, and unprocessed piles of clay, which could have simply been torn out of the soil to enter into a mysterious composition.

Moly-Sabata – Material Extension

Océane Bruel discovered clay as material two years ago, when she participated in the Moly-Sabata residency program in France to prepare an exhibition. The country’s oldest active residency program, Moly-Sabata was founded by the cubist artist couple Albert Gleizes and Juliette Roche in 1927, with hospitality at the heart of their mission. During the Second World War, Moly-Sabata opened its doors for artists in exile. The history of the center includes close collaboration with the long-established pottery workshop Poterie des Chals. When Bruel visited it, she bought 40 kilograms of clay.

In the end of March 2020, shortly after her arrival, a total lockdown was declared in France. Instead of sending all participants home, the Moly-Sabata organization proposed to all artists an extension of their residency periods until the incalculable end of the lockdown. Bruel decided to stay. With all exhibition plans put on ice, she had plenty of time. And lots of clay. She started to explore the material and its potentials for her practice, upon which the accidental extension of her stay would have a great effect.

After All, Maybe

In the early 1990s, the number of artist residencies started to increase rapidly, boosted by the period’s increasing global mobility and digital interconnectivity. Many of these new programs propagated the liberation of artistic labor; some in fact created great opportunities for artists, whereas others were rather to burnish institutional agendas for image reasons. In 1995, the first Guide of Host Facilities for Artists on Short-Term Stay in the World was published in France. [1] The criteria for including an organization in the guide were relatively simple: “the provision of workspace for research and experimentation, and the encouraging of creative activity through contacts either with other artists or with a specific environment.”

Today, many residency programs are institutions in their own right, with their own practices, identity, and history, but they also comprise active parts of hybrid networks of diverse social and academic institutions, universities, private companies, museums, and public-sector institutions. While residencies remain a part of the art world that is mostly invisible to the public, they have long been part of the field’s complex process of value creation. The right residency may well increase the market value of an artist, not only as a line it a resumé but through new contacts and networks. Beyond that, though, the value of an artist residency is hard to grasp and even harder to measure. More often than not, the actual outcome or gain does not become manifest as part of the program. However firmly fixed as a line in an artist’s resumé, the residency itself is, above all, a matter of lived experience and, as such, a relatively incalculable factor for whatever is – in this context – considered a success. Impossible to exhibit, the most valuable results of a residency – close connections, disruptive moments, temporary dislocation, or unfamiliar impressions – unfold only with time. The acknowledgement of an open-ended, essentially unpredictable process is a crucial part of the equation.

Irmeli Kokko is a Helsinki-based cultural producer and educator who has acted as the initiator, director, and curator of various international residency programs. While working as a lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts of the University of the Arts Helsinki (2006–18), Kokko was responsible for the Academy’s Resident Fellow and Alumni Residency programs. She has conceived international seminars, conferences, and symposia on art residencies and has written and edited the essay compilation Contemporary Artist Residencies – Reclaiming Time and Space (2019, Valiz) together with Taru Elfving and Pascal Gielen.

Image caption: Courtesy of the artists

Notes

| [1] | Association Française d'Action Artistique, L’accueil d’artistes en résidence temporaire dans le monde / Guide of Host Facilities for Artists on Short-Term Stay in the World (Paris: Association Francaise d'Action Artistique, 1995) |