BOOK OF REVELATIONS? Barbara Reisinger on "The Andy Warhol Diaries" (Netflix 2022), directed by Andrew Rossi, produced by Ryan Murphy

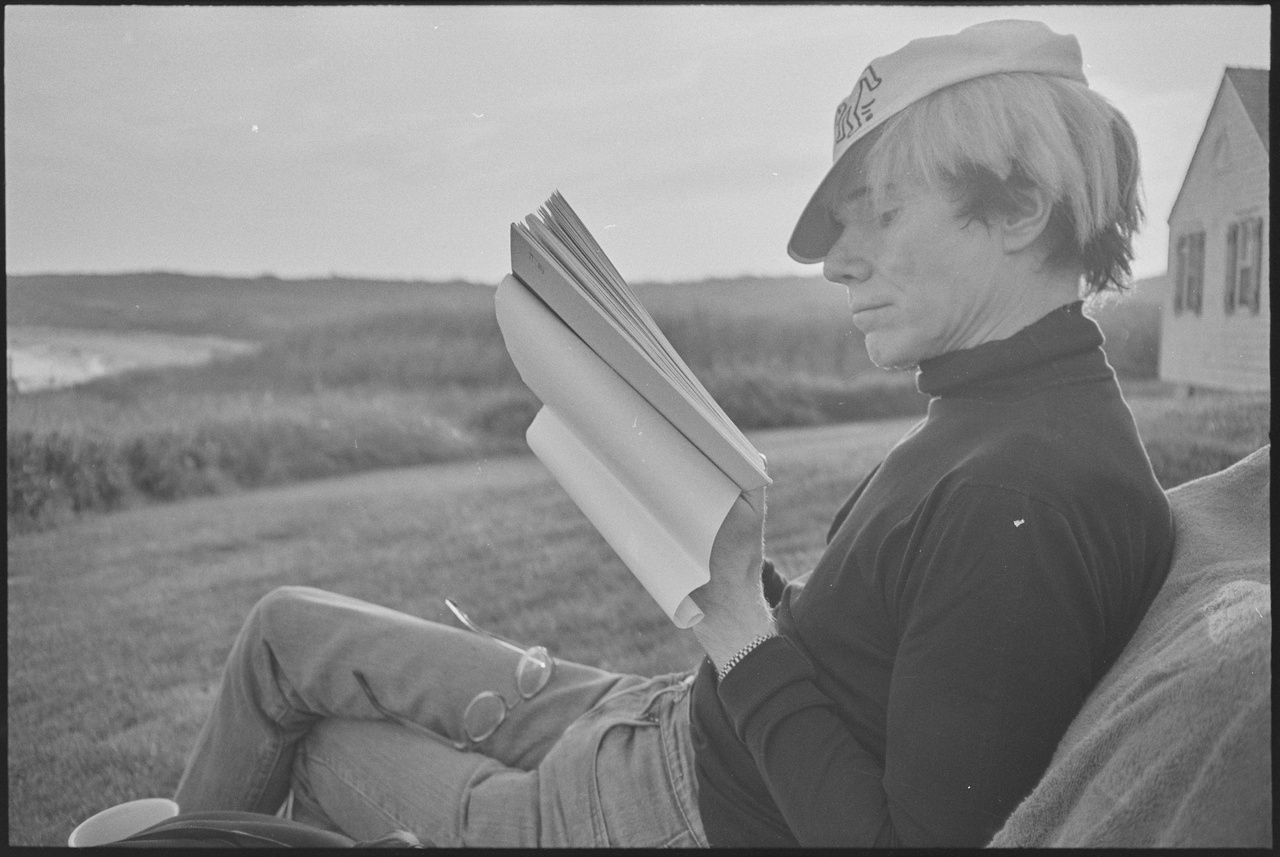

Andrew Rossi, “The Andy Warhol Diaries,” 2022, film still

A fellow Warhol scholar once told me that he read through the entire 807 pages of The Andy Warhol Diaries when it came out in 1989 in hopes of learning something new. He was thoroughly disappointed. No doubt, as a queer art historian, he was intrigued by the prospect of reading more on Warhol’s life and art through the beginning AIDS crisis that was, at the time of the book’s publication, still ravaging the US, but he learned more about the artist’s cab fares. The 2022 Netflix series based on Warhol’s diaries does acknowledge that the book was a disappointment to some, but it also insists that you can peer behind Andy’s carefully maintained persona if you only know how to read the diaries. “It’s not so surface,” says Benjamin Liu who worked with Warhol from 1982 to 1986, “if you read between the lines.” [1]

This is an old myth about Warhol perpetuated by the Netflix adaption of The Andy Warhol Diaries: that there is a hidden truth about the artist which “no one wants to talk about,” as Warhol Museum curator Jessica Beck likes to put it. [2] This purported truth is what the series promises to reveal to its viewers, and – spoiler alert – it mostly encompasses Warhol’s intimate relations. Thus, the series is arranged around the artist’s relationships with three men. Two of these men are romantic interests: the first is interior designer Jed Johnson, who appears as a fixture in Warhol’s life at the beginning of the diaries book; the second is Jon Gould, an executive at Paramount whom Warhol “tries to fall in love” with after Johnson leaves him. [3] The third relationship is of a more complicated nature, hovering uneasily between mentorship and exploitation, friendship and erotic attraction, as Warhol becomes admirer, collaborator, and later even landlord to the young and increasingly troubled Jean-Michel Basquiat.

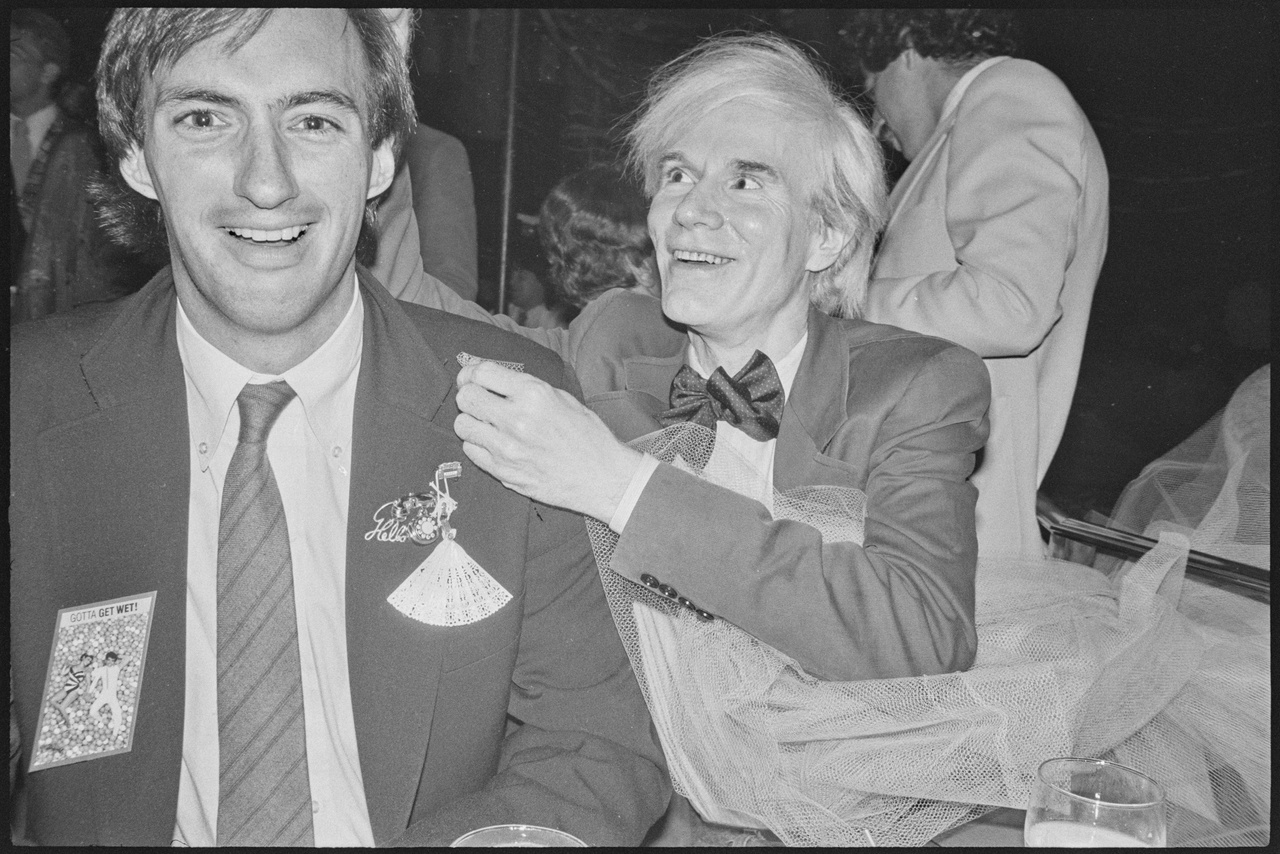

Andrew Rossi, “The Andy Warhol Diaries,” 2022, film still

Tragedy looms large in Rossi’s retelling of Warhol’s later life. The events recounted in the series kick off in 1968, even though the first entry in the Diaries dates from November 24, 1974. The year of Warhol’s near-fatal shooting by Valerie Solanas supplies more gravitas to the persona presented: a perpetually sad, lonely man past his prime who fills the void inside himself with ever more extravagant pastimes and relies on his young partners to fulfill overblown romantic expectations of stability and emotional security. The last episode cements this focus on melodramatic tropes of love and evanescence in an almost absurd review of the tragic deaths of all our protagonists. After Gould’s and Warhol’s untimely passing, Basquiat overdoses in 1988, and Johnson falls victim to a plane crash in 1996.

In Warhol’s life, however, tragedy peaks in 1986, as he, by then in his 50s, outlives Gould, who succumbs to AIDS-related illness at only 33 after a protracted struggle. This single event seems to set the tone of the whole series. It remains heavy throughout, as if constantly anticipating disaster and loss. The impending sense of doom solidifies in the penultimate episode, in which viewers are reminded that the period leading up to Warhol’s own death in February 1987 was marked by the anxiety and grief of the AIDS crisis. In the book, Warhol’s diary entries are gradually colored by underlying panic as he mentions rashes on the skin of acquaintances and sudden hospitalizations and deaths of party guests, celebrities, and friends but does not discuss HIV head-on. Yet the adaption takes on the subject in depth, not only for the drama but also in a genuine effort to reevaluate the common perception that Warhol shied away from AIDS as a political crisis. While phobic comments – Warhol was afraid of catching HIV from an unshaved Calvin Klein whose stubble might pierce through the skin of a pimple [4] – are pondered, we also learn that, in spite of Warhol’s intense fear of hospitals since his 1968 shooting, the artist visited Gould every day when he was treated for pneumonia in 1984. [5] This is where the production is at its most nuanced: it does not resolve the tension between an image of a cold and petty celebrity who tries to shield himself from the sick and less privileged, and the rightfully terrified, aging gay man whose insecurity is exacerbated by what we would call his “high-risk” status. [6] The existence of both traits in tension allows for a complexity in the understanding of Warhol’s life and persona that is at other times relinquished in the pursuit of the “true” Andy Warhol.

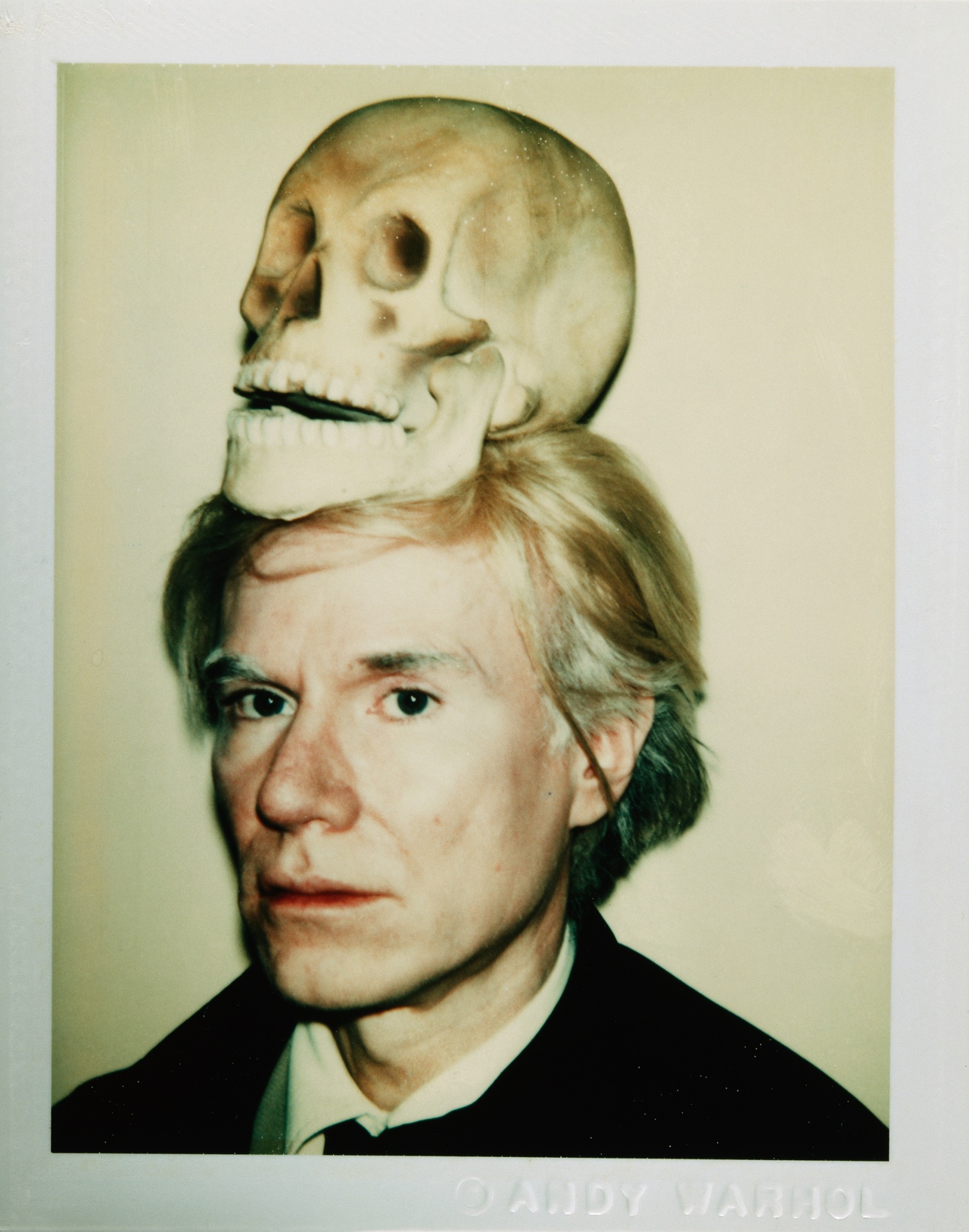

Andrew Rossi, “The Andy Warhol Diaries,” 2022, film still

The series’ notion that there is a singular truth about Warhol, hidden beneath the surface, is contradicted by many statements made on the show but at the same time continuously upheld by its confessional tone and the way it tries to imbue the diaries with authenticity. The diaries were transcribed from daily phone conversations between Warhol and Pat Hackett, whom he had initially hired as a secretary and who had already worked on the earlier Warhol books The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975) and POPism (1980). Hackett’s editorial agency is addressed in the last episode but, rather than looking at the ways in which Warhol spoke through a multiplicity of voices, the show tries (and fails) to find a clear line between Warhol’s and Hackett’s voices. The wonderfully Warholian tool of an AI-constructed voice employed to read from the diaries becomes a stamp of authentification in the hands of the producers. Generated from just three minutes of recordings of Warhol’s actual voice, it nevertheless suggests that we hear Andy voicing his innermost feelings, as the AI voice is often introduced in blurry shots of an actor in a silver wig, whispering into the phone, wandering lonely through the delicate interior of Warhol’s East 66th Street townhouse. [7] The voice is beautifully sad in its monotony, and the scenes where it is laid over archival footage are often the most touching, gently amusing, even sublime. However, its unified tone falls short of conveying the unsettling ambiguousness of Warhol’s voice and persona which apparently left listeners guessing what, if anything, he was expressing. In the words of two Belgian journalists who spoke with the artist in the mid-1970s: “It is impossible […] to give testimony of this infra-voice, of this slightly nasal vocal effacement, of this white noise, of this gentle withdrawal that retains nothing but a fleeting warmth drifting away. Sinatra between the sheets. The voice of a cosmonaut in zero gravity, distant and muffled as it is filtered through space and machines, yet close to the heart and mind.” [8]

Warhol’s countless strategies to achieve ambiguousness and opacity, which he employed deliberately, carefully, and at times anxiously, are treated only as layers to peel away. [9] The revelatory discourse of the Netflix series makes hardly any mention of the artist’s skillful use of confessional formats – diary, interview, recording – to shift and shape his images. Warhol consistently turns the drive to uncover intimate truths on its head through the strategic banality and sheer number of his “revelations,” the gossipy tone of his delivery, and the use of proxies to speak on his behalf, to mention but a few of his tactics. The series employs its own share of obscurant techniques, but with a different epistemological aim. Earlier publications are not referenced, but nevertheless used. Only in reading along to the melancholic flow of the AI voice, one can find that single sentences to full paragraphs from POPism and the Philosophy are woven into the text sourced from the diaries, presumably to supply a semblance of emotional depth where the diaries seem to fall short. [10] The streamlined verisimilitude of the Netflix version of Warhol belies the hybridity of his voice.

The show’s refreshing proposal to shift the focus away from the celebrated 1960s and take a serious look at Warhol’s later work and persona is undercut by its appetite for revelation and tragedy. The potential of the show’s serial form, and much of its more than 6.5 hours of screen time are wasted on repeated efforts to unearth truths about Warhol’s gayness, his casual racism, his hesitant stance on AIDS, and his purported sense of sadness and failure. All of these topics are more than worthy of examination but do not comfortably fit the framework of the somewhat clichéd, decadent, and lovesick character we encounter in Rossi’s The Andy Warhol Diaries.

The Andy Warhol Diaries, 6 episodes, written and directed by Andrew Rossi, 2022, on Netflix.

Barbara Reisinger studied philosophy and art history at the University of Vienna and is currently a research associate at Universität Stuttgart. In her PhD project, she focused on Andy Warhol’s wallpapers as an artistic medium.

Image credit: © Andy Warhol Foundation/Netflix

Notes

| [1] | The Andy Warhol Diaries (Netflix 2022), directed by Andrew Rossi, produced by Ryan Murphy, episode 5, 44:09–44:29. |

| [2] | The Andy Warhol Diaries, episode 1, ca.18:00. |

| [3] | Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, ed. Pat Hackett (New York: Warner, 1989), 372. The Andy Warhol Diaries, episode 5, 42:30–42:50. |

| [4] | Warhol, Diaries, 515. |

| [5] | Warhol’s visits are not mentioned in the diary entries because “[Jon] made [Andy] promise not to put anything personal about him in the Diary.” However, there is a note from Pat Hackett, explaining that Gould was admitted to the hospital on February 4, 1984 (Warhol, Diaries, 552). |

| [6] | Nine organs had been damaged in Solanas’s attempt on Warhol’s life. He never fully recovered from the extensive surgery that saved him. See Blake Gopnik, “Andy Warhol’s Death: Not So Simple, After All,” New York Times, February 22, 2017, Section C, 3. For a detailed depiction of the surgery, see Blake Gopnik, Warhol: A Life as Art (London: Penguin, 2020), 1–3. |

| [7] | On the procedure of “cloning” Warhol’s voice, see “How Resemble AI Created Andy Warhol Docu-series Narration Using 3 Minutes of Original Voice Recordings,” Resemble AI website. |

| [8] | Pierre Sterckx and Vincent Baudoux, “Andy in Paris,” Plus moins zero 4 (March 1974): 7. My translation. |

| [9] | On Warhol’s tactics of queer opacity, see Nicholas de Villiers, Opacity and the Closet: Queer Tactics in Foucault, Barthes, and Warhol (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2012), 89–116. |

| [10] | Whenever Warhol’s AI voice talks about love in the first episode, the quotes are pulled from Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (New York: Harcourt, 1975), 45-46, 48, 50, 55. |